Weed and Hawai’i have gone hand in hand in the collective mindset for years. Maui Wowie, Kauai Electric, Puna Budder, and Kona Gold are just some of the varieties that have been long associated with the islands. Hawaiians call cannabis pakalolo, which translates to something like “numbing tobacco.” According to Honolulu Civil Beat, the first documented use of cannabis in the Hawaiian Islands appeared in the Hawaiian language newspaper Ka Nonanona in the year 1842, although it is safe to assume that the people knew about cannabis before the newspapers did, so cannabis use probably goes back much further. That source even goes on to say that there were printed advertisements for medical cannabis in Hawaiian newspapers throughout the 19th century. That came to an unfortunate end when Hawai’i was colonized.

Today’s landscape isn’t much better, though. In 2000, Hawai’i became the eighth state to legalize medical cannabis and the first to do so through an act of state legislature, as opposed to ballot measure. The law allowed medical card holders to cultivate their own plants, or designate a caregiver to do so. It was another 15 years, however, before consumers could purchase cannabis at the dispensary, and those rules were deemed “temporary.” Not much has improved since then.

Challenges From The Environment

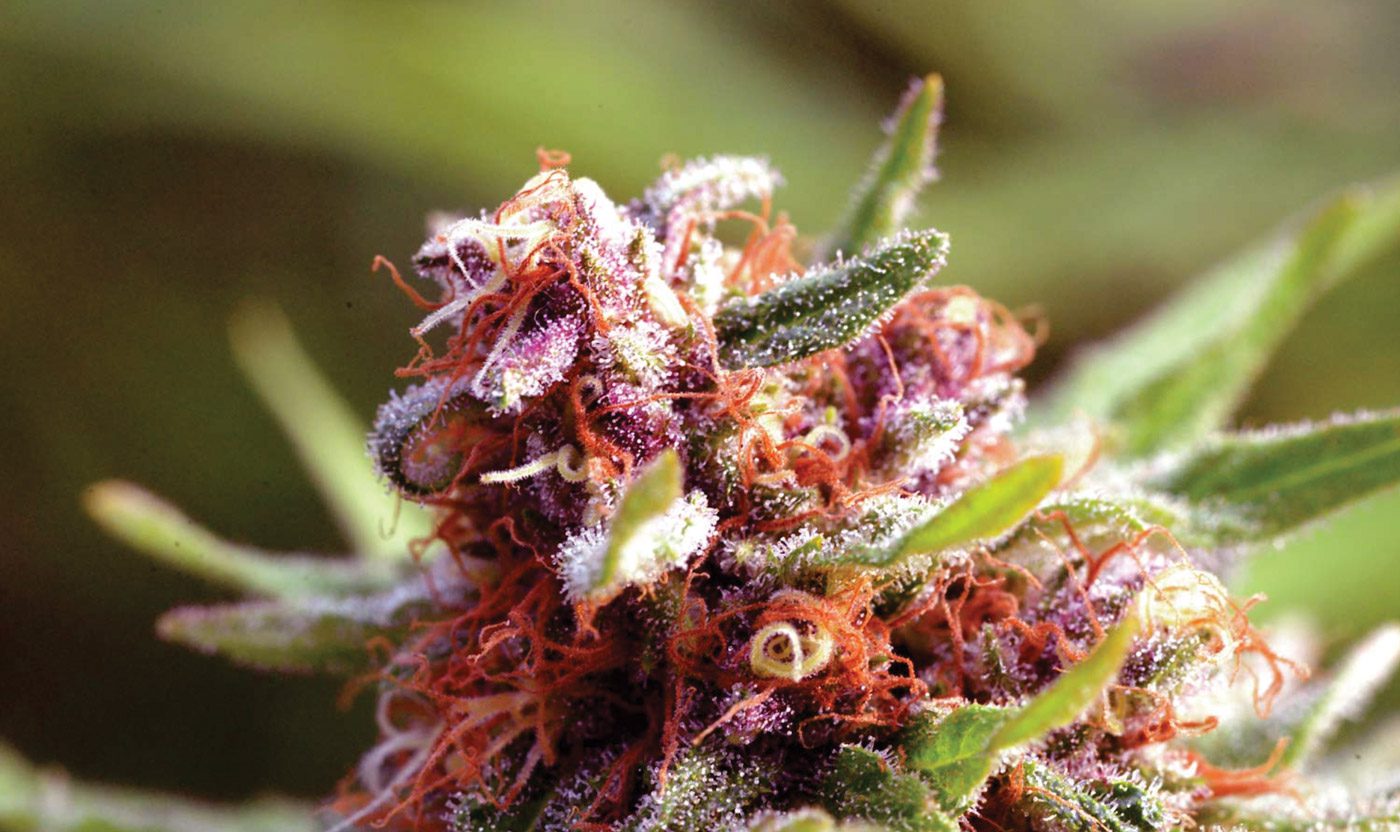

Growers in Hawai’i face challenges from the environment as well as from the legal system. Will Grinnell is a grower and breeder in Maui who helped spearhead the Maui Cannabis Guild, a non-profit designed to help legalize cannabis in Hawaii. After moving from the Northeast to Maui with his family in 2010, Grinnell slowed down on his music booking business, Origins Music International, to focus on cannabis genetics. He is cofounder of cannabis genetics research and production company Sticky Finger Seeds and helped co-found Deep Green Agency, a cannabis advisory firm, which Deep Green Genetics is a part of. Deep Green Genetics is a family of cannabis breeders that offers a unique and rare collection of cannabis genetics. Deep Green Genetics is also a subsidiary of Earthdance, which is celebrating 25 years of multi-location peace events around the globe.

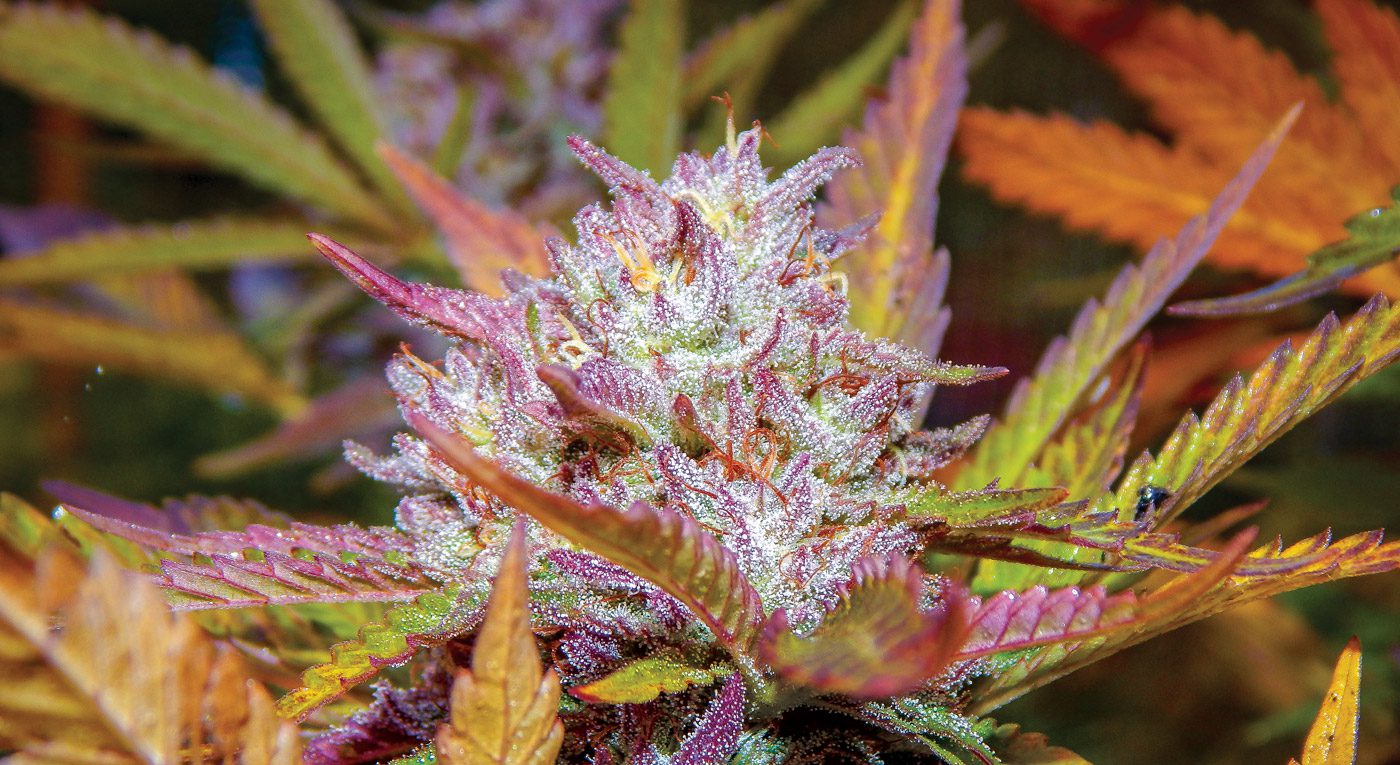

Grinnell grows at about 300 feet, which is considered basically sea level. At that range, you see a lot of the vegetation you think of as being tropical, like vines and flowers, citrus and avocados, and coconut palms. With even a small elevation increase, he says, you get into a different climate that’s more like a Northern climate zone. Grow and breeding partner Ben Brodie lives at 3,200 feet, where the plant shows very different expressions due to the exposure to lower temps. Grinnell is subject to a little bit of the maritime winds and sea salt, but that’s usually only an issue for people who are growing within a half-mile or so of the shoreline.

“We have an agricultural legacy here that is at least a couple hundred years thick,” says Grinnell. “And we also have 10 of the 14 known climates in the world.” It’s said that on Hawai‘i Island you’ll find all 10. Throughout the islands, you won’t find climates like tundra or permafrost, of course, but you will find plenty of climates like tropical, moist subtropical, and moist continental — the key word among most of them being moist.

“The headlands are where the ocean and the land meet,” says Grinnell. “But it’s not like California, where in a place like Santa Cruz County a garden that is within a mile of the coast will be dealing with huge humidity changes, fog, and temperature changes, wind, and so many other variables. Here, along the seaside, it’s not like that. It’s pretty calm.”

Grinnell’s part of the island catches a persistent tradewind from the Northeast. He says his part of the island is lucky to catch this steadily blowing breeze because it’s like a fan that keeps the garden happy. Grinnell grows in both outdoors in the sun and in greenhouse structures. “You’ll certainly see better results growing under a membrane of sorts, to stop the heavy rain damage, but sungrown for sure,” he says.

Grinnell uses agricultural poly weave in his greenhouses, which diffuses the light. “The light becomes more even and it seems to help develop more of an even growth,” he says. “But what it really does is help with the rains.”

Once your flowers start maturing, you have a short window of time in which a lot of things can go wrong. Of course you might have outdoor flowers and get lucky with no rains. “But if it rains and it’s heavy and you’re not undercover it will beat down the brix and wear off some of the sharpness of it and it will look a little more like typical outdoor pot.”

Their setup is more like a lean-to, with a cover but open to the air so that wind can get through. No climate controls. Grinnell says some growers are repurposing restored floral greenhouses that are more sophisticated, but you can be very successful without that kind of a setup.

A Perfect Laboratory

Are there any things that growers in Hawai’i have to deal with that other growers might not face? “A million!” says Grinnell with a laugh. “I learned from other master breeders who have been established here for a generation or more that we are the perfect laboratory for finding out what your problems are and fixing them. In other words, the air is very rich with pathogens here.”

Until Grinnell moved to Maui, he didn’t know that cannabis could develop powdery mildew — it was something he had seen only in tomatoes. “Marijuana didn’t get,” he says. “It simply wasn’t a thing.”

Hawai’i has what’s called superbugs. They deal with spider mites and aphids and the usual suspects, but Hawai’i has developed into a special case. Particularly in the lower elevation agricultural zones,

there’s been contamination from the old sugar cane and pineapple plantations that have been in existence for the past almost 200 years. Monsanto, which is now owned by the pharmaceutical company Bayer, conducts extensive research in Hawaii on seed production for its GMO corn. Grinnell says lack of regulations means that Monsanto can perform open air testing and open air experiments that Grinnell says have created pesticide-resistant superbugs. (In December 2021, Monsanto pleaded guilty to 30 environmental crimes related to using a glufosinate ammonium-based pesticide called Forfeit 280 on corn fields in Hawaii, and then allowing workers to enter the field during the restricted period, and also pleaded guilty to illegal storage of a banned pesticide.)

“We have some big problems growing pot here and superbugs is one and pathogens are the other,” Grinnell says. “But I’ve learned to use those problems to my advantage so that I can breed the best genetics in the world that have a DNA that’s resistant to these things, because they’ve had to face them so many times over.”

Light Sup

Unlike West Coast growers in California who often have to do some sort of light dep, Hawaiian growers have to “light sup.” “We don’t get the long summer nights like the mainland does,” says Brodie, who marketing manager at Deep Green Genetics. “We have to supplement light to create the 18/6 cycle that the plant needs to stay in a vegetative state. Nothing fancy, just a few clamp lights will do. Due to our position on the Earth we can flower outside all year round so that when we remove the lights we will be ready to harvest 45 to 55 days later. Our strains are bred to be fast finishing so we can complete five cycles a year.”

Grinnell says that outdoors in Hawaii it is a flowering environment for cannabis 12 months of the year, but they don’t quite get the 14 hours of daylight that it takes to really trigger a plant to flower. In November, December, and January, the sun is noticeably weaker. “We get up to 13 and a half hours in the summer and we do get some stretching in June near the solstice,” says Grinnell, “but what we have in the greenhouse is some simple lighting that comes on to keep the plants awake, to keep them in veg, on a normal 18-hour cycle.”

Grinnell speaks to a misconception that the genetics they’re working with are called “equatorial genetics.” That’s not the case, he says, because that would mean that they’re simply growing in one season outdoors and the plants were acclimated particularly to a humid environment. “But we grow in greenhouses and we do light sup so it’s very natural, but it also does imprint in the DNA of our genetics the same way that anyone else’s genetics that you would buy is triggered to that light cycle,” Grinnell explains. “So they’re ready to grow indoor or outdoor or anywhere; it’s not equatorial.”

Since growers are not dependent on springtime sun and they can add lights as needed, they can harvest at many different times in the year. “Which makes us pretty lucky,” says Brodie.

“If we don’t take a day off and don’t go to the beach, we can do five cycles in the calendar year,” add Grinnell. “I certainly have slowed down from that kind of aggressive growing and sometimes even five cycles a year is a big push, but you can do even more than that.”

But they’re breeders, so they’re not trying to grow for volume. However, growers here who are growing aggressively get at least three times the volume in the same square footage in July, August, September than they do in the winter months. “I mean, literally three times as much or three times less,” says Grinnell, “so that gives you an idea of how the strength of the sun does change here quite a bit between the solstice and the equinox.”

Relocating to Hawaii

Jeff (who requested that his last name not be used), owner and grower at Dragon’s Flame Genetics, moved to Hawaii two years ago from Oregon. He acknowledges that he’s one of the “white guys” that native or long-time growers probably get resentful of, because he’s new to the area. Before that, he lived in California in his teenage years and grew for nine seasons in Oregon. He says Hawai is a tough place with a lot of challenges. But, he says, when the sun is shining there are very few places that are more beautiful. He left California before recreational laws passed because the price of real estate had skyrocketed so much. He thought he would be able to work a season or two and then save up enough money to buy a place. “Then rec hit,” he says. “Money being under the table made it really hard.”

In a spur of the moment decision, he decided to buy a piece of property he found for sale in Hawaii. After saving every penny for a year, they flew to Hawaii with a dream. They did find a place to buy, but then reality hit . . . yes, property is cheap in Hawaii, but there’s no infrastructure to make it work. Jeff got an education in YouTube to build a small house. “The property we bought was bare,” he says. “It had a house that had burned down so it had a cesspool but nothing was livable. It’s still kind of glorified camping right now.”

Jeff and his wife, Melissa, live off the grid, with rainwater catchment and solar power and a generator, along with a refrigerator where he safely stores his seeds. They too grow in greenhouses and do light supplementation. “I’ve got one permanent veg greenhouse that I run lights in in the middle of the night, so they don’t flower, and then I have another greenhouse that I move the plants into when it’s time to flower,” he says.

Jeff’s microclimate, about a half hour from Hilo, is a true tropical jungle, and it’s tough, he says. With no frost, pests don’t die. Dragons Flame Genetics grows at 1,000 feet. On their side of the island and half-way up a mountain, it’s wetter and colder than in Hilo, which is closer to the water and is generally warmer. “We get 200 to 450 inches of rain in a year and almost every night we hit 95 to 99% humidity. During the day it’s pretty rare for us to get under 80%.”

His biggest fights are with fungus, bud rot, and stem rot. They also have a pest called bark boring beetles, which burrow into the stem itself. Once embedded, they crawl the whole way up the stem eating along the way. The beetles are covered with fusarium spores. “Once they have fusarium they’re going to die,” he says. “The biggest challenge is keeping moms.”

One way of managing the beetles is to use a pheromone lure, but that could also mean that you’re attracting the neighboring population of beetles to your plants. He says he has dialed in his IPM regimen but it’s a constant challenge. “I’ve had more challenges here than anywhere I’ve ever grown, so you’ve definitely got to be on your game. In California you could miss a spray, but you can’t get away with that here.” Jeff says growing is his life’s work, and his intention is to grow as organically and sustainably as possible, because he loves cannabis.

Grow With Respect

Mr. Aloha (his Instagram handle) is a native Hawaiian grower who is 25 years old. He’s been growing for around 13 years under the mentorship of other elder growers and is now a recreational grower. “My parents didn’t really have a green thumb so I’m very blessed to be able to start learning and growing at such a young age and have my trials and tribulations growing in such a crazy environment, you know?” he says.

He says he tries to explain the challenges to other growers here, who sometimes just don’t get it. “You’re constantly fighting off the tropical weather,” he says. “You could be hot one day and storming the next. Some people just run indoor, some people use lights. Both have problems, it’s just about how much you want to push to get what you want.”

Mr. Aloha lives on a four-acre farm with power and water. He raises red wigglers, fishes, and hunts, and makes his own fertilizers.”Organic is the way to go,” he says. He supplements with lights when he needs to but usually just grows with the season. He says he lives “in a little crevice” on the west Maui mountains, on the oceanside. As we talk, roosters crow in the background and he’s outside tending to his vegetable garden. He’s in between the beach and the mountains, a perfect location that is protected from salty winds but still receives the ocean breeze.

A nearby river is his water source for the plants. As a recreational grower, he’s focused on what his patients tell him they want. If they can’t sleep, he grows Indicas. If they want to have a productive work day he sticks to Sativas. In 2018 he ran a 52-strain pheno hunt and narrowed down to seven. “I’ve adapted to the conditions here by getting different strains, adding different soil, trying different fertilizers,” he says. “I’ve seen the best outcome growing amending the soil and growing in that, and maybe adding a little molasses at the end, maybe a little mineral powder.”

At the time we spoke, he was growing Dutch Treat, Gorilla Glue #4, Blue Dream, Crack Head, and some of his own crosses of local strains. He harvests about two pounds a month. “I’m not growing to be big,” he says. “It’s for my patients and for my ability to keep improving as a grower.”

Hippies and Soldiers

Maui Wowie captured attention back in the 1960s. And going forward decade by decade, even people who didn’t smoke knew Cheech & Chong’s jokes and what “Maui Wowie” referred to. It’s obvious to think that non-Hawaiian growers would have sought out Hawai’i because of its remoteness and privacy, but there’s more to it than that.

“There was definitely an expatriate and hippie thing in Hawaii of people going there to get away if that’s what you choose to do,” says Grinnell. “Certainly back in the ’70s you could very much disappear here and a lot of the cannabis influence that I saw here did come out of the hippie community here in Maui, which grew when Jimmy Hendrix came out here to film ‘Rainbow Bridge’ and so forth. That brought a community here that never left. And that was sort of the beginning of one thing, but really the cannabis genetic lineage goes straight to the military.”

Turns out service members have never been very good about following orders to not smoke weed. Honolulu was a very strategic location for our military. During the Vietnam war, American service members were getting Thai and Lao seeds. “I know there was Laotian varieties being grown here as early as 1965,” Grinnell says. “From the history that I know, that was the first version of what people on the mainland were getting that was called Maui Wowie.”

Hippies had the Michoacan genetics and soldiers had the Laotian genetics and that’s what became established in Hawaii, and Maui in particular. Maui and the Big Island are still the two main cannabis growing districts in Hawai’i, and this is how it all started.

Jeff says the old-time growers he knows are still growing the classic stuff. “Skunk Dawg is a big one here because it handles the mold and fungus, and people have used her to breed with for at least 15, if not 20 years now,” says Jeff. A lot of what people think about as mainstays like Puna Butter, Maui Wowie, and Kauai Electric are lost to most people, he says. “Cuts are hard to keep here,” he says. “People are breeding with them and calling them the same thing for the tourists, but it’s not.”

Because the humidity is so high, old timers have come up with very creative ways to dry flower. Jeff says that if you roll a joint and don’t light it right away, it will absorb moisture from the air and become un-smokeable within five minutes.. He says people use “crazy off-grid tech ways” to dry, like running little propane burners with a cast iron pan, using dehydrators, even using a solar cooker to harness the sun. “With varying degrees of quality coming out of those efforts, compared to curing in a cool, dark, and slow way,” he says. “The moral of the story is not everyone has the infrastructure that they would like and you just figure out how to make something that can be smoked.”

The Future of Hawaiian Growing

With Hawaii’s agricultural legacy and branding power, the cannabis industry there should be among the strongest in the world. But it’s not. Grinnell says the ingredients are there to support microbusinesses, but the lawmakers have not been getting the job done. “They should be held accountable,” Grinnell says. “But things are going to change. We’re about to get rid of a whole bunch of administrations. Our governor is as useless and un-progressive as they can come. But the reason I go into this is because we live on the land of native Hawaiians. This is an occupied Kingdom and the native Hawaiians are really getting screwed by the lawmakers.”

The cannabis industry is one that could help everyone here and most importantly the native Hawaiians. So, Grinnell hopes that when things do change, the social equity mentality will prevail and Hawaiians will have the first chance to enter the industry. “People all over the world already know about our legacy of growing here so when things do change and federal laws change and we’re allowed global trade, there are going to be a lot of benefits to people here,” Grinnell says. “Especially when we can already back it up with a triple A product, which we’re very good at growing here.

Mr. Aloha says the legacy of growing in Hawaii has changed a lot over the years, but the old ways of doing things are still there. For instance, he has uncles who will push their cows through fields to make sure they eat the grass around their 8- or 9-feet tall plants growing in their pastures, the way they have been doing it for 80 years. And, he says, old strains are still there if you know the right people and have good influences around you. “Growing in Hawaii is flourishing, but it’s different,” he says. “A lot of younger growers don’t want to grow their grandparents’ strains because there are so many different new strains out there that they want to get their hands on. A lot of growers aren’t breeders. They’re just really out there to get that gas, to get those nice terpenes.” Mr. Aloha says he will always grow what his patients want, but, he also likes to see what the island’s history still has to offer.

Mr. Aloha says he’s still trying to figure out what he wants the future of legalization in Hawai’i to be, but he knows he wants it to be more localized. “I want to see more people that’ve been living here for 20 to 40 years being able to grow and produce for their families and for local distribution instead of for people who are just throwing money here and don’t even live here,” he says. “And there are people who think they’re just going to grow something in Hawai’i and then be successful. Outsiders don’t understand that it isn’t easy here and things go slowly.”

He says people sometimes get gung ho and plant 150 plants, then lose them all to rust mites. Or they don’t respect the very land that they’re on. “You should be pulling off the most organic, non-GMO weed that you can get without spraying chemicals all over the place. Soil in Hawaii is still living soil so just grow with what Mother Nature intended,” he says. “Don’t come out here to grow if you aren’t willing to keep at it even when you want to quit and you’re not willing to talk to the locals.”

He wraps up our call by trying to decide if he should go surfing or do some more farm chores. “Today is a major surf day,” he says. “But I gotta buckle myself down.”