Cannabis use by humans has been going on since before people started writing things down. As such, details are sketchy, and some educated guesswork is involved in trying to reconstruct our shared long history and the evolution of cannabis consumption. What we do know, which I’ve outlined below, is based on current archaeological thinking, and some details may well change as new archaeological data is available.

The history of cannabis use points to its cultivation over centuries. Cannabis sativa, as many will agree, is a very useful plant. As a species, it is thought to have evolved during the Miocene period around 28 million years ago. For perspective, Homo sapiens (modern humans) are thought to have only been around for about 300,000 years or so.

Early humans were nomadic hunter-gatherer-scavengers who appreciated cannabis’ usefulness. Cannabis sativa has particular attributes that made it popular for early people to gather and eventually cultivate, although maybe not the attribute that first comes to mind.

Attributes of Cannabis

When mature, cannabis seeds are comparatively easy to separate from their flower clusters, a trait that has been utilized throughout the history of cannabis use. Cannabis seeds can be eaten raw, toasted, crushed into a porridge, or pressed to produce oil. They are a source of calories, protein, fat, fiber, and vitamins. They can also be used in animal feed.

Another useful aspect of cannabis is its fiber. Cannabis is a “bast” fiber, which means that the fibers form in long strands. Bast fibers are made from collecting the long phloem cells, which are the transport system used to move sugars and organic compounds from the leaves to where they are needed. Lucky for early humans, these bast fibers can be extracted fairly easily using primitive technology:

First, the cannabis stalks are gathered. Prime harvest season for fiber is in early flowering, but fiber can also be extracted from the plants after they have mature seeds, a practice that ties into the history of cannabis use for its diverse applications.

The stalks are then “retted.” Flax, and jute, which are two other plants that have been used for their fiber throughout the ages, are also plants that can be retted. Retting prepares the best fibers for removal from the rest of the plant material.

The stalks are either left in a pile for “dew retting,” or left to soak in a body of water for a week or two for “water retting” techniques. Either way, the plants begin to rot, which allows bacteria to break down the chemical bonds holding the stem together, and this allows the bast fibers to be separated. Careful monitoring is required to collect the bast fibers once the stalks have retted enough to soften them, but before decomposition degrades them.

The retted stalks are allowed to dry. Then the central woody core is broken and removed, either by hand or by crushing between hard objects. The fibers are separated from any remaining material, and collected for further processing.

At this point, the fibers can be twisted into rough cordage. Strands are put together in a lengthwise bundle, and the ends twisted in opposite directions. The middle point will buckle, and twist together naturally.

Then, additional material can be added to the free ends as needed and twisted until a cord of whatever length desired is made. This twisting can be done by hand (making a loop at the center to wrap around a toe or branch can be helpful). Rope can be made by using a similar twisting method with several strands, a technique that is also part of the history of cannabis use for practical purposes.

As an alternative to making cordage or rope, the fibers can be “carded” in preparation for making string or yarn. This process aligns the fibers parallel to each other, and removes any remaining contaminants. Carding can be done with tools as primitive as sharp sticks in a bundle, or some sort of stiff comb or brush. The modern equivalent uses two paddles that resemble dog brushes that are used for the same effect.

After carding, the fibers are in fluffy lengths called “slivers,” which are similar to carded wool or other fibers. String or yarn is made by twisting and adding fibers as needed. This can be done by hand, by using a wooden shaft with a disk near the bottom called a “drop spindle,” or as the technology improved, the spinning wheel (as featured in the Rumpelstiltskin tale).

Regardless of the method, the resulting fibers are wound around a shaft called a spindle. The threads can then be used for a variety of purposes including weaving cloth, a testament to the evolution of cannabis consumption for both practical and cultural uses.

Farming Cannabis Seeds

Collecting cannabis for seeds and textiles was certainly a worthwhile endeavor. Once people started farming, they naturally included cannabis if seeds were available, contributing to the history of cannabis use.

Humans started intentionally growing plants during the First Agricultural Revolution of around 10,000 BCE. The domestication of Cannabis sativa is thought to have started in Asia at about the same time, along with the intentional breeding of both improved fiber (hemp) and “effect when consumed” (cannabis) varieties. It appears that the “effect when consumed” part gained a lot of popularity around this time, although exactly when people started consuming cannabis to get high isn’t known.

The evolution of cannabis during this period is still debated. Pottery embossed with cannabis imprints has been found from the Yangshao culture (5,000 BCE) in Asia, further contributing to our understanding of cannabis evolution.

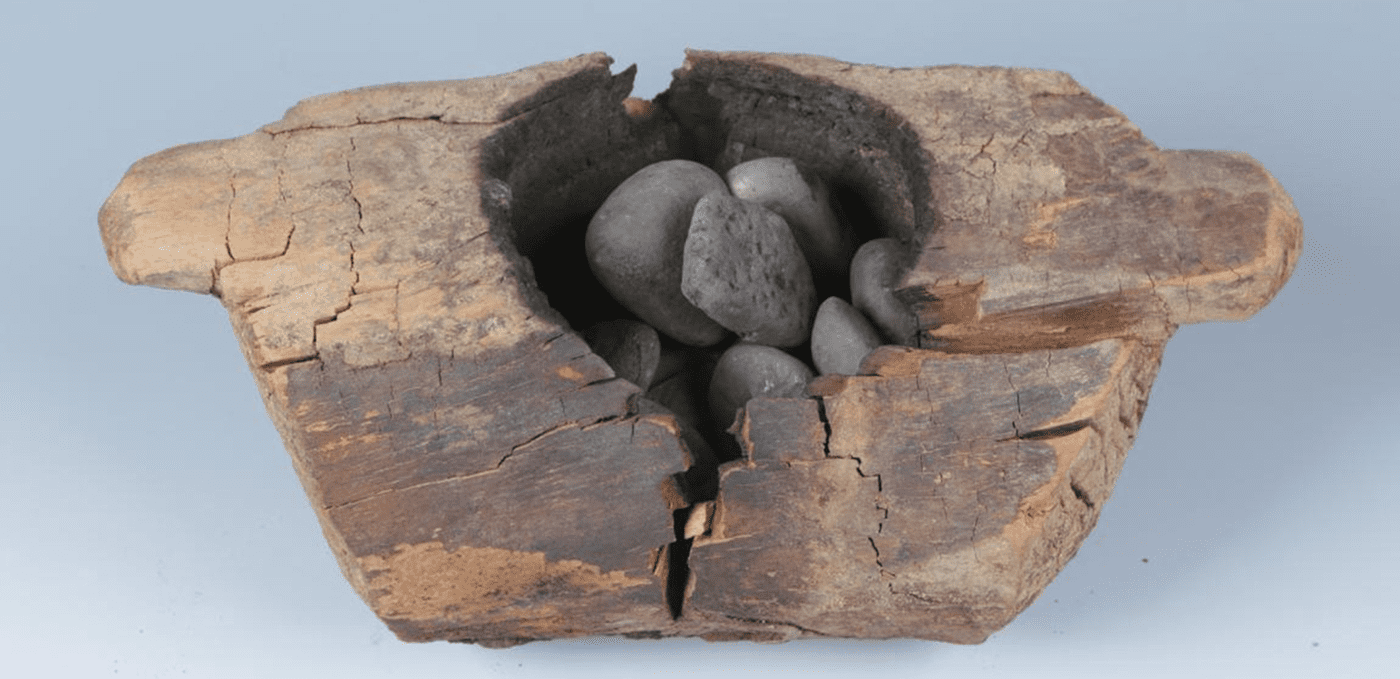

We know for sure that at some point folks started figuring out how to get high from cannabis, since ancient “hotboxing” and “vaping” was a thing. While modern people might gather in a car or a closet to spark up a few joints and “hotbox,” our ancestors didn’t bother with going small. At Jirzankal cemetery in western China, artifacts from around 2,000 BCE were found that suggest that they made use of closed spaces with wooden braziers which were filled with cannabis and hot rocks to release either vapor or smoke (depending on how hot the rocks were) for inhaling.

Modern cannabis consumers tend to be dismissive of cannabis consumption that predates their own lifetime, but one might imagine the looks someone today would get at a party if they pulled out a BBQ, filled it with a few pounds of weed, and then put scorching hot rocks from the oven on top to vape out the whole room at once.

Speaking of ancient consumption and some of the old, old school crew — when many folks think of early “edibles” they think of the magic brownies and infused spaghetti sauce from the ’60s and ’70s if they are old enough to know about them. However, a beverage made from cannabis, yogurt, nuts, spices, and rose water known as bhang and cannabis-infused ghee (cooked clarified butter) were popular in India circa 1,500 BCE. It is 3,500 years later and bhang is still an edible of choice for many, and adding infused ghee is still taught as a method to infuse cannabis into other foods, marking a long tradition in the history of cannabis consumption.

Cannabis For Mental Health

Using cannabis to improve mental health is hardly a new school of thought. In the Vedic text Atharvaveda (meaning “knowledge storehouse of the procedures for everyday life”) written around 1,200 BCE, cannabis is listed as one of the five sacred plants that can “deliver us from woe.” This marks an important moment in the history of cannabis use.

Apparently, the hotbox thing worked out well enough for people to keep doing it. In 425 BCE the Greek historian Herodotus wrote in The Histories. Book 4, Chapters 73-75:

“After the burial, the Scythians cleanse themselves as follows: they anoint and wash their heads and, for their bodies, set up three poles leaning together to a point and cover these over with wool mats; then, in the space so enclosed to the best of their ability, they make a pit in the center beneath the poles and the mats and throw red-hot stones into it. The Scythians then take the seed of cannabis and, crawling into the tents, throw it on the red-hot stones, where it smolders and sends forth such fumes that no Greek vapor-bath could surpass it. The Scythians howl in their joy at the vapor-bath.”

Although the passage only mentions seed, one might suppose that some of the seed covering and perhaps associated flowers were added as well, reflecting cannabis consumption for both recreational and spiritual purposes.

Early medicinal use is documented in the (possibly mythical) Emperor Shen Nong’s pharmacopeia Shen Nong Ben Cao Jin (“The Divine Farmer’s Materia Medica”). The book is a compilation of oral traditions attributed to Emperor Shen Nong (2,800 BCE), and formally documented around 250 AD. This underscores a pivotal moment in the evolution of cannabis as a medicinal tool.

It mentions some possible effects of getting high:

“Ma Fen (cannabis) is acrid and balanced. It mainly treats the seven damages, disinhibits the five viscera, and precipitates the blood and cold qi. Taking much of it may make one behold ghosts and frantically run about. Protracted taking may enable one to communicate with the spirit light and make the body light. The seed is sweet and balanced. It mainly supplements the center and boosts the qi. Protracted taking may make one fat, strong, and never senile. Cannabis Sativa is also called Ma Bo. It grows in rivers and valleys.”

When many modern people talk about the history of cannabis use, they often start with the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, with some comment about jazz singers who smoked cannabis before that. Many younger folks consider only the advancements in cannabis from the last couple of years to have relevance, but the fact is that humans and cannabis share a lot of history over thousands of years, and that cannabis evolution should be cherished and respected.