The world population has grown from 1.6 billion people in 1900 to approximately 7.8 billion today. It is estimated that by 2050, food production will need to increase by roughly 70%.

You might ask, “What does this have to do with soil health?” Or more specifically, what does this have to do with cannabis? The answer is insects and insect “frass,” their poop. Insect farming is solving the increasing global food demand while reducing agriculture’s negative environmental impact to the earth and soil. The best part for farmers is that the insect’s highly efficient conversion of biowaste into biomass also yields a waste stream consisting of molting skins (exuviae), and most importantly for us growers, microbial and nutrient dense insect feces (frass).

I first heard of insect frass at a TED talk given by Pat Crowley of Chapul Farms in 2018 (view that talk here: youtu.be/QsASL5hizMA).

He spoke about black soldier flies (BSF), insect proteins, and his global effort to reduce agricultural waste. What first grabbed my attention was using the circular system of insect farming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and waste while creating a byproduct, frass, that proves beneficial for organic farming, soil regeneration, and carbon sequestering.

What Is Frass?

Frass is a general term that means the things that insects and their larvae leave behind. It contains excrement from all the things they consume as they go along like plant material, wood, human food, and other materials. Frass will look different depending on the insect type and what their food source is. Frass can look like little bits of dust, rust, or sawdust, or whatever the insects have been consuming. Frass also contains chitin, the main component found in the exoskeletons of insects and shellfish. The nutrients in frass are in a readily-available form that allows it to function as efficiently as a mineral NPK fertilizer.

What Is The Black Soldier Fly?

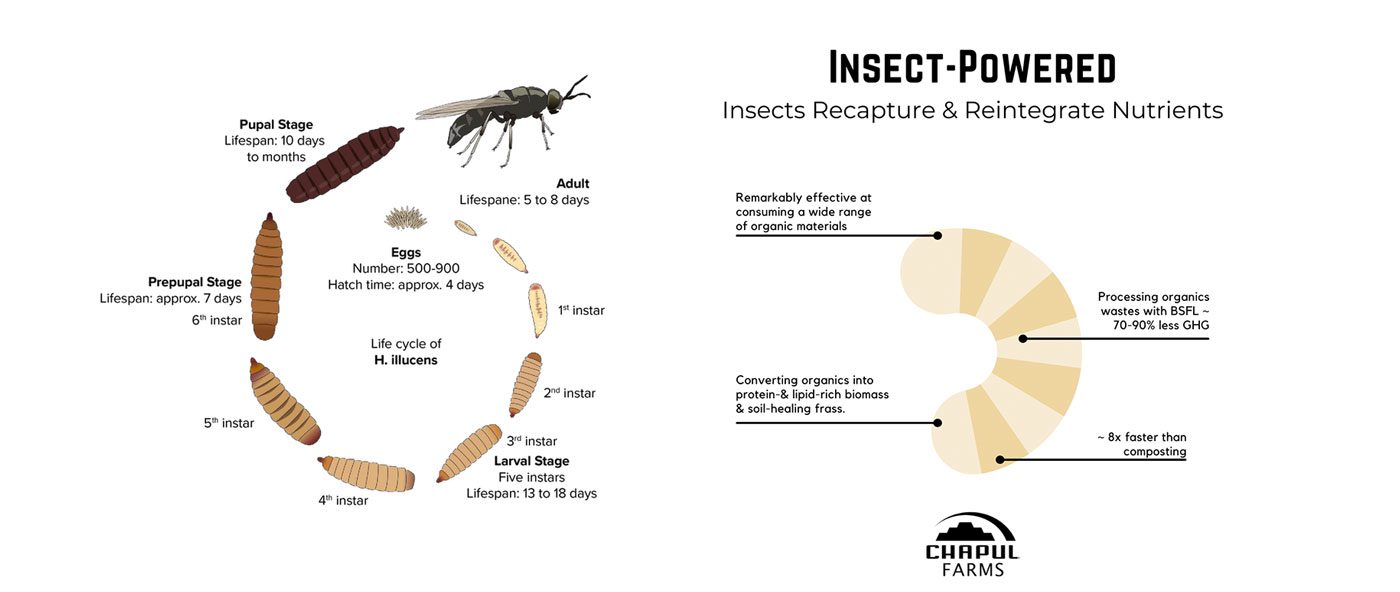

The black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens, BSF) is a common and widespread insect that is originally native to the tropical Americas. It is currently found on all continents. Chapul Farms’s educational material explains that the larvae of the BSF are voracious eaters that feed on a wide range of organic materials from manure to scraps. They are efficient in converting all of that biomass into high quality proteins, lipids, and macro/micronutrients, producing a microbe- and nutrient-rich frass residue.

Because they produce such good stuff, Black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) are a perfect solution for a closed loop agricultural system. Processing waste with BSFL produces 70% less greenhouse gasses compared to composting, according to Chapul Farms (Pang W et al. 2020).

What Can Frass Do?

In further exploring frass and the limited studies that have been done so far, I found that frass is an active soil remediator revitalizing beneficial microbial life, which is the focus of most current regenerative agricultural practices. It is also an NPK source of equal or greater concentration than popular manures and composts. Studies show frass promotes plant growth, increases chlorophyll content of leaves, total length and width of stems, and increases fresh weight of finished product. Because of rapid mineralization and presence of nutrients in a readily available form, frass has shown positive interaction when used in conjunction with immediately available liquid nutrients. Increases in biomass and nutritional content are also due to activation and stimulation of soil microbiota.

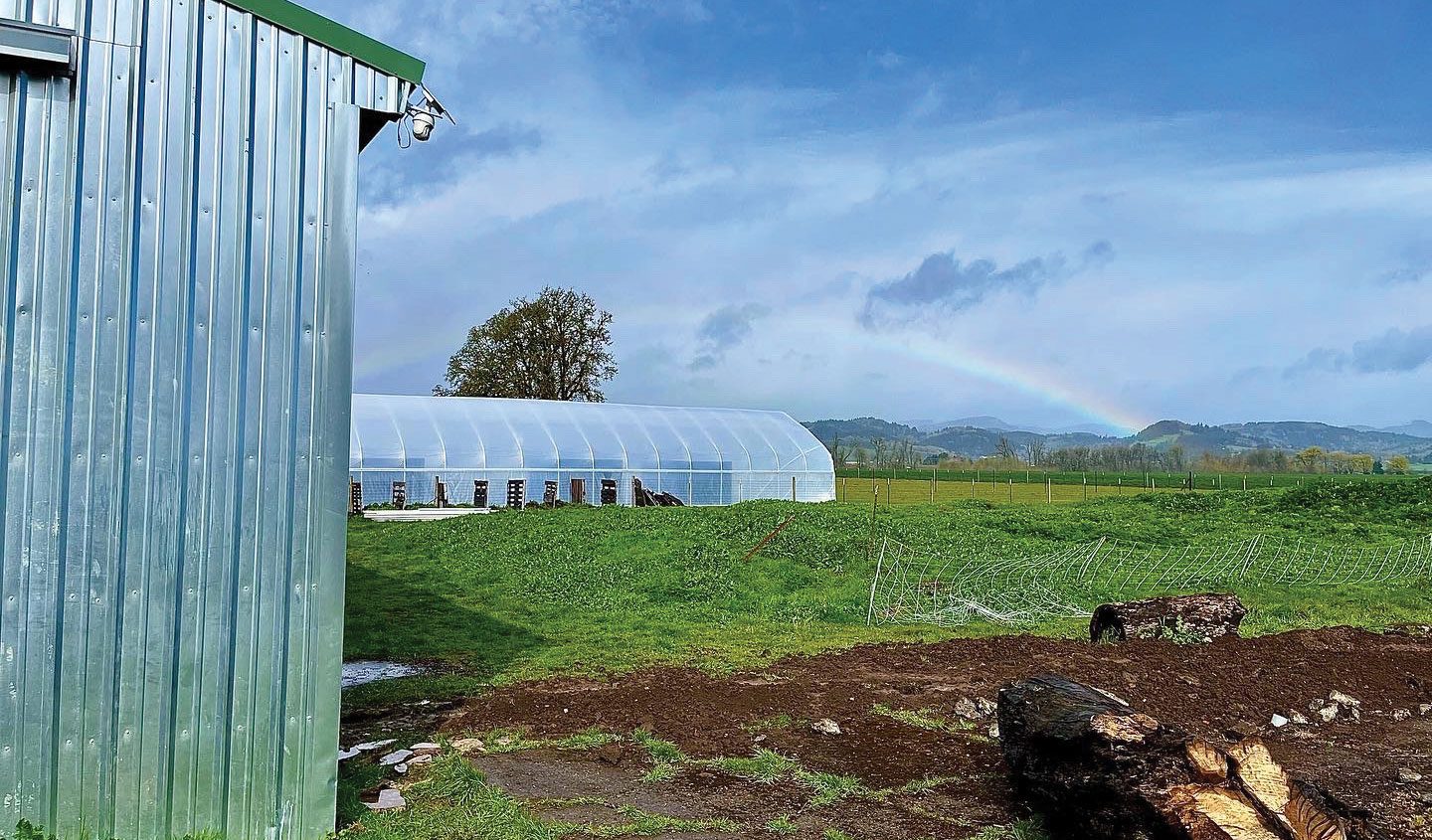

Those of us loyal to the soil know that microbes, fungi, archaea, protozoa, etc. all play a crucial role in healthy soil for nutrient and elemental cycling, carbon sequestering, and the physical and nutritional support of plants. Todd Severson, project manager, and Michael Place, chief technologist, of Chapul Farms, allowed me to view their current test results from their innovation center in McMinnville, Oregon, and what I saw was an amazing array of microbes and fungi. This included bacteria and fungi capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen (N) and solubilizing phosphorus (P) and potassium (K).

The ability of insect frass to promote plant tolerance against different abiotic stresses has been seen in multiple studies. In bean plants specifically, frass has increased the tolerance of seedlings and plants against drought, flooding, and salinity. (Poveda et al. 2019)

If nutrient content and microbial activity isn’t enough to sell you on frass, studies have shown direct action or activation of a plant defense response against pests and pathogens from its use. The triggering of the plant’s defense system is brought on by a polysaccharide called chitin. Chitin is the main component found in the exoskeletons of insects and shellfish and is commonly used in agriculture to deter pests.

In-house Trials Of Frass

As the owner and operator of an award-winning recreational cannabis, hemp, and vegetable farm focused on sustainability, my team and I are always looking to decrease our carbon footprint while bringing the highest quality product to our customers. We have been running in-house trials on frass for the last eight months and have seen drastic improvement in finished product, which has brought us increased market value and greater customer satisfaction.

There is still much to learn about frass. Trials are being run in Oregon and all around the world. It remains to be seen if frass will completely replace chemical fertilizers and pesticides, but based on our trials and current scientific data, I am certain we will see insect frass added as a permanent part of sustainable agriculture.

Jason Lampman is the owner and operator of State 3 Farms and The State 3 System. State 3 is an award-winning micro-tier cannabis, hemp, and vegetable farm located in McMinnville, Oregon, with a focus on organic and sustainable inputs.

Q&A With Pat Crowley Of Chapul Farms

Pat Crowley is the CEO of Chapul Farms. Crowley and Chapul made headlines in 2014 when Mark Cuban invested in Chapul’s protein bar made from cricket flour, the first in the U.S., on Shark Tank. Crowley, a whitewater rafting guide, became interested in the potential of harnessing the protein in insects in 2011 when he began learning about how it takes much less water to harvest insect protein. Chapul Farms was founded in 2018 to focus specifically on black soldier fly larvae (BSFL) applications. Their bigger mission is to transform food systems with insect biology. They have recently set up their Innovation Center in McMinnville, Oregon, where they run trials and gather data. I caught up with him for a quick chat about his facility, frass, and its benefits.

JL: What is the broad vision of Chapul Farms?

PC: Currently, we are building and scaling modular insect farms to do a 180-degree turn from the loss of biodiversity on the planet.

JL: What types of insects are you farming at Chapul Farms, and why?

PC: Right now, we are focusing on the black soldier fly. In our current agricultural system, we have a harvest index of approximately 50%. That leaves around 50% of plant material harvested inedible by humans. With the incredible wide range of plant material BSFL consume, previously determined waste streams that end up in landfills can be diverted into BSF farms to be returned to the circular, regenerative system.

JL: How is it possible for frass to show such a low percentage of greenhouse gas emissions?

PC: Well, the frass goes directly back into the soil. If we’re looking at a 14-day cycle, the plant biomass enters our system, and 14 days later potentially goes right back into the soil as an amendment. Even using the next best case scenario, aerobic composting, you’ll see a 70% reduction in carbon based emissions by having the material pass through a BSF farm as opposed to composting because there’s essentially no methane production associated with insect consumption.